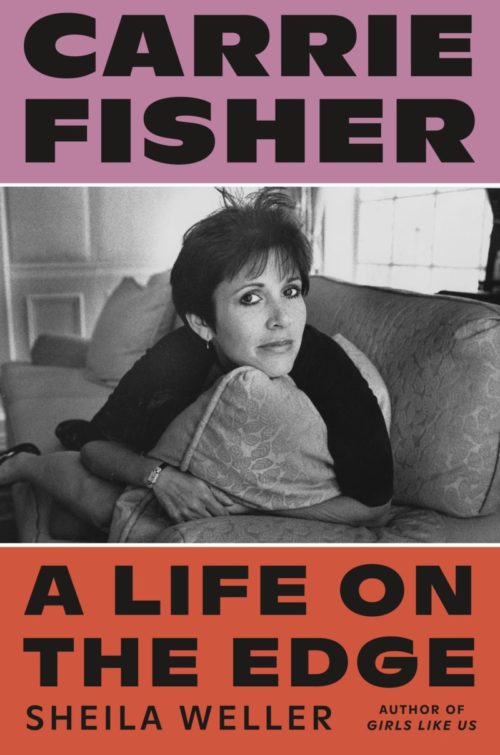

Women’s eNews sits down with Sheila Weller to discuss her new book, Carrie Fisher: A Life On The Edge:

WEN: Why did you choose Carrie Fisher to write about?

SW: I love writing about complex, iconic women who have changed or resonated with the culture, and she is high in both categories. I loved her revolutionary book of “faction” (as she calls fact plus fiction), POSTCARDS FROM THE EDGE, was always admiringly and fascinatedly aware of her role as a social magnet and adored friend and wit in Hollywood and ALL areas of the cultural world.

I also shared a Beverly Hills – entertainment industry childhood with her. Mine was non celebrity, but there were parallels and intersections: Her mother Debbie Reynolds, as an MGM teen starlet, snuck into my uncle’s glamorous Sunset Strip nightclub Ciro’s to learn to be worldly; my movie-magazine-editor mother wrote many stories about Debbie and Eddie and then Debbie and Eddie and Elizabeth Taylor. We lived around the corner from them and, briefly, when my mother delivered an article she’d written about Debbie, we once went over to their house.

And, most pointedly, my own family had a non-celebrity but not-un-public version of her family’s Debbie-Eddie-Liz scandal: a beautiful woman breaking up a marriage, with drama, publicity, and violence. My mother and I were the female cast-offs of a man we both loved, with bonding and veiled mutual humiliation, not unlike what I sensed, and learned, Carrie and Debbie felt.

But, mostly, Carrie was a badass feminist heroine hiding in plain sight: so peerlessly honest and witty about her life’s madness and challenges and sexism that she relieved other women who felt shamed by their own upswinging weight and age, and perhaps their crazy families. When she died on December 27, 2016, the world erupted in grief and admiration, and the Princess Leia posters held aloft by the hundreds at the subsequent Women’s Marches proved and fortified her significance – her adored stature. People LOVED her – not just her many dozens of highly accomplished and also regular-Joe best friends, but a mix of Americana from STAR WARS super-fans to the highest-barred feminists.

She simply had to be written about.

WEN: How easy/difficult was it for you to find people to speak with you about her?

SW: It was challenging. Many people were private or protective of their memories and I didn’t push them – I respected their reticence. But a good number of her close friends – including familiar names – and colleagues from different movies and projects and brushes with her in their lives were happy to open up. When you have to go after sources and they’re not handed to you on a silver platter you find many unexpected major sources who can identify key moments, episodes, interactions and character revelations that you might not otherwise find.

This adjoining excerpt, of Carrie’s time in drama school in London, is an example. I found about ten people who knew her there, during a transformative but little-known year of her life. Others didn’t look.

WEN: Was there anything surprising that you learned about her while researching and/or speaking to others about her?

SW: I knew she had major challenges – inherited propensity to drug addiction and bipolar disorder. She has certainly written and spoken about them. But I guess I didn’t realize the extent of her vulnerability, because she often wrote and spoke and performed about her life with such witty hauteur and aplomb. She was achingly vulnerable, despite her reputation as her time and place’s Dorothy Parker. Her friend from drama school and beyond, Selina Cadell, said, “She was as fragile as a butterfly.” Along with the opposite – an almost intimidating wit – this was true!

I also was aware that she de-stigmatized bipolar disorder and mental illness in general, but I wasn’t aware of how greatly and bravely she did so. She really was a force in wresting the shame from the conditions, especially for women.

WEN: How did writing this book compare to writing your previous books (i.e. Girls Like Us)?

SW: Like every child is different, every BOOK is different. With Girls Like Us, my focus was music heroines and way pavers who broke the ‘50s rule that you had to get married after college, who became romantic adventurers, who mirrored and narrated their generation by writing on that and many other female ‘60s generation landmark issues and moments. With my next book, The News Sorority, the focus was on women with more settled personal lives (both families of origin and eventual partners) but whose professional lives were full of challenges as they pushed past the sexism and other roadblocks involved in reaching the highest levels of news reporting and anchoring. With this new book, it is just one woman, and her challenges, in a way, were more complex and intense than those of the others. Empathy is always what I aim for when I write. Each book requires a different kind.

WEN: How do you feel about Carrie’s family denouncing the book?

SW: Honestly, it didn’t feel good. I am not a gotcha journalist or a Kitty Kelley. (I wish I were one fourtieth as tough as she!) I hope it doesn’t sound too self-serving to say that empathy is an important tool I like to think I use.

I respect and admire the courage and dignity of Carrie’s family. I will say that I did contact them, through their representative, several times, and tell them about my book contract and respectfully request their participation. But I am not going to argue with their interpretation or remarks.

As I said in the statement to the L.A. Times and other media, it was my deep admiration of Carrie that prompted me to want to do a biography of her in the first place. I will also add that every single review has mentioned how positive my book is toward her. Booklist said it was “profoundly sympathetic” and “a worthy tribute. To a strong, intelligent woman.” USA Today called it “admiring.” Kirkus said the reader had “300 pages to fall in love with Carrie Fisher” and that even if the reader didn’t follow her when she was alive, the reader would still “miss her” when they finished the book. Library Journal called it “thoughtful,” “absorbing,” and “poignant” – a “portrait of a brave, complex woman” (other reviews used very similar if not identical words). Newsweek called it a “heartfelt tribute and beautiful homage.” Publishers Weekly said I “celebrated her for her wit and strength.” They may certainly choose not to read it but these reviewers and many readers have found it positive.

BOOK EXCERPT:

Carrie wanted to be an actress, not a singer or nightclub performer like her mother (and father). And among those in the London Palladium audience, in late July 1974, watching Carrie wow the audience with her singing, as part of her mother Debbie Reynolds’s show, was George Hall, head of acting at London’s Central School of Speech and Drama, long the “second” drama school in London after the prestigious Royal Academy of Dramatic Art (RADA) but catching up to RADA now, and quickly. Lyall Watson, a Central teacher who would go on to head up RADA, was there in the audience with George, and he remembers George going backstage to, in Watson’s sensing, be “vetted” by Debbie. Debbie wanted Carrie to apply to Central, and Debbie was checking Hall out. The reason for the vetting? Carrie had already auditioned for RADA and had been turned down. Central might have to prove itself to not be sloppy seconds.

Central was not the school one would automatically pick for a cosseted movie star’s daughter. It was known for its left-wing leanings, and it had a talented, competitive, but decidedly non-elite student body: tuition was cheap; it was state subsidized. But now, under George Hall’s direction, everything was changing. Its reputation was suddenly overtaking that of the reigning RADA. As one former Central teacher, Alan Marston, recalls, “In 1974, Central was definitely the best training for any young actor.”

Central was a product of the 1930s Bristol Old Vic school, “which produced the young actors that shook up the postwar theater. It was very left-wing working-class, not this glamour thing, not this MGM-back-in-the-day thing,” says Christopher John, who would be a student there with Carrie. Its cachet was its selectivity—it accepted only twenty-six freshman students a year—and its effective emphasis on getting students jobs. Rare for England at the time, “Central achieved about 95 percent employment of students within a year of graduation,” John says. “At the time, in the U.K., you couldn’t join Actors’ Equity unless you were already employed with the regional repertory theater companies.” But Central somehow gotits graduates into rep companies. Clare Rich says, “At the end of our three years we wanted jobs, and Central made that happen. Most of us went straight from school to rep. We weren’t rich, so working right away was huge.”

Central was situated in the old Embassy Theatre in a section of London known as Swiss Cottage, not far from the Irish Republican Army’s stomping grounds, and the 1970s was the time of the IRA protests and bombings and cease-fires. Vanessa Redgrave, a Central alum, and her brother Corin Redgrave would come to Central to give impromptu speeches as members of the Workers Revolutionary Party.

Central’s audition process involved two speeches—a Shakespeare monologue and a contemporary one—followed by a series of improvisations. At the end of the improvisations, you learned whether you had been accepted.

Carrie traveled to Central for her audition, and she got a sense of the school. There was the infamous Canteen, the hub of activity between classes, run by the matriarchal Marianne, a strongly accented Romanian scolder (when you were in her café, you behaved yourself!) who served “fairly disgusting” coffee, as one alum recalled it, and liver sausage rolls and cheese and tomato rolls, wrapped in cellophane. And there was her more accommodating husband, Gerry, who ran a proper but drearily menued restaurant upstairs. Marianne and Gerry’s was where everybody congregated. The food was crap, but there was little choice, except to walk down to the Cosmo, the Eastern European café on Finchley Road.

Shampoo – the Warren Beatty-starring and co-written movie in which Carrie had her first role as a precocious Beverly Hills teenager –was not released yet. That would come in February 1975 — but George Hall knew about Carrie’s role in it. Still, her audition was handled, as all Central auditions were, by the proprietary head of admissions, an elegant elderly woman known simply as Miss Grey, whom the actress Deborah MacLaren, then a Central student, recalls wielding great power but being “tiny, birdlike, imperious, with a gray chignon; she looked like she’d just stepped off a ballet stage. We had all these fantastic old eccentric ladies fluttering around, and Miss Grey was a major one.” Miss Grey gave Carrie Fisher the official good news: she was “appointed” one of twenty-six students entering Stage ’77. (The classes were named for their graduation date, three years hence.)

Carrie’s response was not uncomplicated. Initially, she was gratified. Still, in the late summer of 1974 there might have been fear of the unknown. Drama school in London was a good choice; it meant Don’t be a movie star’s daughter. Take acting seriously! But this would bring out her insecurity, and she might well have sensed this.

And perhaps she understood that an epic showdown with her mother was what their long push-pull relationship was heading toward and that fighting over attending Central was a handy igniter. Whatever the reason, shortly before she was set to fly from L.A. to London for Central’s orientation week, Carrie told Debbie, “I’m not going. I’ve decided to stay home. I want to stay in Los Angeles and decide what I want to do.”

Mother and daughter had a whopper of a fight. Debbie in New York screamed at Carrie in L.A. that she had “no training and no education.” Those five words would pain Carrie for a long time; she was, she would later admit, “very insecure [that I] dropped out of high school to be a chorus girl.” Still, Carrie dug in her heels: I am not going!

“No,” Debbie retorted. “You’re going to do this or you’re going to have to support yourself.”

Carrie, eventually, angrily conceded.

“She was so angry” when she boarded the plane. “I felt sick,” Debbie said. “I’d lost my little girl.”

“Carrie sort of sidled into Central,” Deborah MacLaren, who was a year ahead of her, says, remembering the early September 1974 first day of school. (Today Deborah is a working actress with her own British production company.) “We knew she was going to come—the ‘Hollywood starlet.’” There was reliable rumor that she’d already shot a few scenes in a yet-to-be-released major movie. “So we were all slightly excited and wondering what she was going to be like. I remember looking at her staring at the notice board to see what the next set of casting was in this rabbit warren of a building. She came past me and she was all covered up. It was a warm day, but she was wearing this drab raincoat and this knitted hat that looked like a tea cozy, terribly unflattering. My feeling was she was hiding and wanted to be the least significant person there.”

“She just kind of mucked in,” says then-Central teacher Lyall Watson of Carrie’s unprepossessing entrance. “There wasn’t anything ‘I am Debbie Reynolds’ daughter!’ about her. She was very quiet—mouse-like. Not in a bad way—some Americans come over to the English drama schools and attack them, and she wasn’t like that. Carrie was vulnerable.”

“I was the youngest student there,” Carrie has explained, something that others noted, and “it was the first time I actually lived on my own. I was finally away from my mother (whom I’d happily live off but not with) . . . where no one could be disappointed in me.” She also arrived, she said, “carrying more freight” than the other students, because people knew she was a movie star’s daughter. She said she consciously tried to minimize that.

But beyond the attempt at minimization, there seemed to be genuine insecurity. “She was a lost girl—I felt that very strongly,” MacLaren continues. “She wasn’t a smiler; she never seemed to smile. She was a solemn little thing, not the sassy American we were expecting. She looked as though she needed a bloody good hug, and I don’t know how good Central was for pastoral care. Here we all were, middle-class students from Labour families. I got the sense that she was at sea—surrounded by confident young folk, singing, sitting on stairs, kissing the teachers, in the middle of IRA territory—we were doing that. It was the ’70s! I got the feeling she wanted to hide.” She became friends with a stunning girl named Lucy Gutteridge who was intense and emotionally complicated. In the casting-specific way of Central, Lucy was Stage ’77’s “‘beautiful girl’ and Carrie was the “ordinary girl,’” Christopher John believes.

Whereas most of the students lived with their parents or with roommates in ramshackle make-dos, Carrie had a lovely apartment she’d sublet from a friend and was often driven to school by a chauffeur (something she has said she was embarrassed by and hated. Carrie began giving parties at her London apartment, inviting everyone at the school. This approach—brandishing great, indiscriminate generosity—was unusual at Central and caused curiosity and opportunism. Who else did this? the Central faculty rhetorically wondered. “I remember the parties she used to throw in Chelsea,” says Barbara Griffiths (known to one and all as Bardy), the voice teacher who taught a very eager Carrie “standard English.” “Carrie was an extremely lively, very likable person. She had a twinkle in her eye, and what stood out was her youth,” Bardy says. Bardy was gobsmacked by “Carrie’s innocence in giving those parties. Nobody else had parties where they invited everyone in school!” Deborah MacLaren saw the contrast strongly. “She was a lost girl who also had these glamorous parties; the party thing was part of her neediness. I thought, ‘What is she doing? Wafting around in that silly hat and throwing these lavish parties!’ It was about wanting friendship. I don’t know who her real friends were, aside from Lucy.”

Carrie’s indiscriminate generosity was promptly taken advantage of. Right before Christmas, she gave a big party, and one rowdy fellow picked up the grand piano in the apartment and pushed it out the window! Fortunately, no one was standing on the street in the wee hours of the morning when the massive piece of furniture hit the sidewalk with life-crushing force. But a large monetary fine was inflicted on Carrie, as well as police attention. The incident buzzed around the school the next day, with the students “thinking it was a huge joke; ‘oh my God, how naughty, how hilarious!’” says MacLaren. But the young instructors who attended—Bardy, Lyall Watson—felt worry, shock, and sympathy for naive Carrie.

The day after this catastrophe was when acting student Selina Cadell met Carrie for the first time; “ran smack-dab into her” might be a better description of their encounter. Selina happened to walk into one of the school’s cloakrooms and was stunned to find “the American girl,” which was all she knew about this young student, “crumpled in a heap on its floor, crying her eyes out.” Selina was hit in the face with Carrie’s pain, and that dramatic first encounter would color her feelings about Carrie from that day forward. “People tended to exploit her because she was so wealthy,” Selina would later say, those people’s attitude being “‘Well, who cares if we spill champagne on the carpet or push the grand piano out of the window?’ I sympathized with her and I think she found that unusual. I didn’t know about her background when I was smoothing her ruffled feathers. She never played a grand game or pulled rank. She was just a lovely person with this amazing sense of humor. And she was immensely generous.” After they became good friends, in one of many gestures “Carrie paid for me to come stay with her in the U.S. when I had absolutely no money.” For years Selina was fighting off Carrie’s reflexive generosity. “We think of sharp, witty people as being very resilient, but she had a striking softness and vulnerability.”

EXCERPTED FROM CARRIE FISHER: A LIFE ON THE EDGE BY SHEILA WELLER. PUBLISHED BY SARAH CRICHTON BOOKS, AN IMPRINT OF FARRAR, STRAUS AND GIROUX, NOVEMBER 12, 2019. COPYRIGHT © 2019 BY SHEILA WELLER. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

About the Author: Sheila Weller is a best-selling author and award-winning magazine journalist specializing in women’s lives, social issues, cultural history, and feminist investigative. Her previous books, including the New York Times bestseller “Raging Heart,” have included well-regarded, news-breaking nonfiction accounts of high profile crimes against women and their social and legal implications. Her sixth book was the critically acclaimed “Girls Like Us: Carole King, Joni Mitchell, Carly Simon — And The Journey of a Generation,” which was on the New York Times Bestseller list for eight weeks, and has sold over 170,000 copies. She has won nine major magazine awards, including six Newswomen’s Club of New York Front Page Awards and two Exceptional Merit in Media Awards from The National Women’s Political Caucus, and she was one of three winners, for her body of work, for Magazine Feature Writing on a Variety of Subjects in the 2005 National Headliners Award.