MUDA, Nepal (WOMENSENEWS)–Four years ago, Taruna Badi, 38, a member of the Badi community, one of the most marginalized groups in Nepal, thought her days of prostitution were over.

MUDA, Nepal (WOMENSENEWS)–Four years ago, Taruna Badi, 38, a member of the Badi community, one of the most marginalized groups in Nepal, thought her days of prostitution were over.

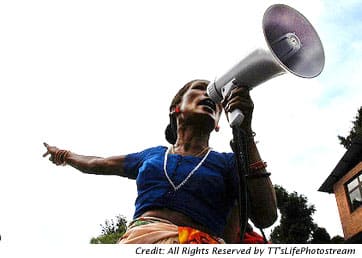

In 2007, she and dozens of other Badi women traveled from Kailali, a district in the far west of Nepal, to Kathmandu, located across the country, to join protests by Badi activists seeking government help to lower longstanding economic and social barriers. For many women, this meant coming up with alternatives to prostitution.

The government agreed to study the Badis’ situation and to provide aid in the form of land grants; employment training; free education for Badi children; health services; citizenship with the caste of their choice; and declaration of the end of prostitution within the community.

But today, many of the women say they’ve barely received any support and have gone back to the only work available to them.

"What else to do?" Taruna Badi asks in desperation. "Prostitution is the only means of earning so far for us."

Badi women say they earn between 70 cents and $2.75 for a sexual encounter.

Binod Pahadi, a member of a government group who recently traveled across the region to assess the situation, agrees with Taruna Badi’s account of the government’s failure to uphold its agreement with the Badi community.

"We roamed across [the] nation," Pahadi says. "Nowhere it is implemented."

Taruna Badi says Badi women need government help because of their lack of education and inferior social status.

A government study estimates the Badi population at just more than 8,000, almost all of whom live in the western part of the country. Nepal’s 1853 civil code categorized the Badi community as the lowest among the socially and economically disadvantaged Dalit caste.

No Alternatives for Survival

"We haven’t had education and hence can’t get any work," Taruna Badi says. "If we try to start a business with the help of loans, customers ostracize our establishments on the grounds that they are run by ‘untouchable’ Dalits. What is an alternative then for means of survival?"

Food is a necessity, she adds.

"Children need to be fed," she says. "There is [not] another source of income. This is the only source of income for us."

Few Badi people own their own land; they live instead in rented cottages by the roadside, on riverbanks and on the forest edges.

Maya Badi, 32, from Doti, another western district, says she left prostitution after the 2007 protests but has since returned to it.

"We have no wealth or property and a family of eight to feed," she says. "It was all right when government and nongovernmental organizations had provided aid [in the form of stipends]. [But once that ceased] we have to see to our own survival."

Now men have once again started queuing outside the houses of Taruna Badi, Maya Badi and their female neighbors.

Mina Badi, 24, Maya Badi’s neighbor, says she has returned to the work and has stopped finding prostitution difficult or uncomfortable.

"What is the use of shame?" she asks.

She says that since her parents live with her, she goes out into the village to look for customers.

"My parents are old," she says. "Therefore, I roam in the village the entire day, eat out and return in the evening."

Prostitution Ban

Various local governmental and nongovernmental organizations in the Badi-inhabited regions have banned prostitution, which has been openly practiced for the past five decades.

But Nirmala Nepali, a member of both the National Badi Rights Struggle Committee and a government committee formed after the 2007 protest to assess Badi rights, says women get around this by going to other villages without such restrictions.

In the absence of other employment opportunities, Maya Badi says the ban worsens women’s lives by making it harder to earn any living.

"The state had agreed to rehabilitate the Badi community and provide employment, but these assurances have been limited to paper alone, and the flesh trade flourishes once more in almost all the Badi-inhabited areas," says C.B. Rana, another member of the National Badi Rights Struggle Committee.

A number of nongovernmental groups have been advocating for Badi rights. One group, Save the Children Norway, a child’s rights advocacy and development assistance organization, has been working to carry out the government’s free education initiative for Badi children.

Some say that although tuition may be waived, some schools are still making it hard for Badi children to attend school because they charge fees for integral programs such as sports and using the library.

Non-Badi women’s rights activists have also spoken up. Both Mira Dhungana, a lawyer, and Mina Sharma, a women’s rights activist, urge the government to fulfill its 2007 promise.

Sharma says that if there is no action soon, women’s rights activists will get more actively involved.

"No woman joins the flesh trade out of mere choice alone," Sharma says. "If the government does not provide the opportunity for Badi women to lead honorable lives like any other Nepali citizen and make necessary employment arrangements for them, we, all women[‘s] rights activists, are ready to actively engage in a renewed protest movement for them."

Would you like to Comment but not sure how? Visit our help page at https://womensenews.org/help-making-comments-womens-enews-stories.

Would you like to Send Along a Link of This Story?

https://womensenews.org/story/prostitution-and-trafficking/110528/nepals-badi-say-prostitution-still-all-there

Nima Kafle joined Global Press Institute’s Nepal News Desk in 2010. She is also a television reporter in Nepal.

Adapted from original content published by the Global Press Institute. Read the original article here. All shared content has been copyrighted by Global Press Institute.