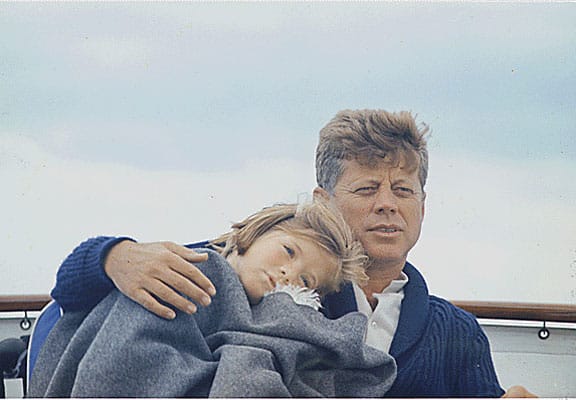

Credit: White House photographer Cecil Stoughton, The National Archives

(WOMENSENEWS)–When the words John F. Kennedy and women are mentioned in the same breath, what usually comes to mind are his tawdry infidelities. But there is another side of the story.

When he spoke the words “My fellow Americans, ask not what your country can do for you, ask what you can do for your country,” young women of what would be called The Kennedy Generation thought he was talking to us. He was our president. We had grown up in the shadow of Harry Truman and Dwight Eisenhower, and politics, we thought, were an old man’s game. Then Kennedy came along and challenged us. Our generation responded.

The Silent Generation, as we had been called, was silent no more. And that included the women among us. His call to public service touched our lives, as well as those of our brothers.

Look at what happed with some of those women.

Madeline Albright became secretary of state; Barbara Jordan became the first southern black woman elected to the United States House of Representatives and received the Presidential Medal of Freedom. Gloria Steinem, a leader of the women’s movement, was just this week among a group of barrier-breaking women to win the Presidential Medal of Freedom. Nancy Pelosi became the first female U.S. House majority leader; Eleanor Holmes Norton is the delegate to the U.S. Congress from the District of Columbia; Senators Barbara Mikulski of Maryland and Dianne Feinstein of California; Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsberg; Attorney General Janet Reno. Diane Nash led some of the most successful civil rights campaigns, including the Freedom Riders and integrating lunch counters in the South.

The new chair of the Federal Reserve, Janet Yellen, was 17 when JFK died.

Some of us went into journalism and changed its face. Our generation led the fight to open up newsrooms to women. Betsy Wade was the named plaintiff of the suit against the New York Times and other women followed suit at the Associated Press, Newsweek and elsewhere.

My best friend in high school, Clare Crawford-Mason, did the first stories for network television on battered women. Nora Ephron was an intern in the JFK White House and quipped–with her usual flair–that the only thing that kept her from a passionate affair with the president was a bad permanent wave. She, of course, went on to become a great filmmaker and playwright.

When Ephron was an intern, I was a young reporter, thrilled to have an office in the National Press Building, working for a small news bureau. The excitement at being so near the nexus of power made up for my meager salary.

Nov. 22, 1963

I remember that Nov. 22, 1963, was a slow news day in Washington. The president was out of town, in Dallas to help iron out a battle between two feuding factions in the Texas Democratic Party.

Near midday, the man who delivered press releases opened the door and said, “There’s been gunfire in Dallas.”

I rushed next door to the UPI office and read on the news ticker the first words of the report by UPI’s Merriman Smith.

Three shots were fired at President Kennedy’s motorcade in downtown Dallas.

I dashed out of the UPI office and ran to the White House. I couldn’t think of anything else to do.

Other reporters had the same idea and we crowded into the foyer near the Oval Office. A TV set was tuned to CBS, where Walter Cronkite came on camera, in his shirtsleeves. A man handed him a piece of paper. Cronkite looked at it, removed his glasses and read, struggling to maintain his composure, “From Dallas, Texas, the flash, apparently official: ‘President Kennedy died at 1 p.m. Central Standard Time. Two o’clock Eastern Standard Time, some 38 minutes ago.'”

One of the reporters in the foyer starting punching the back cushion of a green leather armchair; I just stood in shock, not really believing this could be happening. We didn’t shoot our presidents in America.

I covered the funeral, along with my late husband, Alan Lupo (who would become a Boston Globe columnist). We were given the standard white press badges that said “Trip of the President,” because no one had made up any new ones.

A few years earlier, when I was the editor of my college newspaper, I had interviewed Kennedy when he was a senator. In the middle of the interview in his Senate office, a bell rang that signaled a vote on the floor. He invited me to go with him to the chamber to cast his vote. Heads turned as we walked along, and though I thought I looked pretty spiffy that day in my new dress and high heels, I knew the glances weren’t for me. Heads turned after him like flowers bending towards the sun. We climbed into the tram that ran underground to the chamber, and as I was taking notes, my clip earring fell off and rolled under his seat. He gallantly retrieved it for me. I was mortified! But I swallowed hard and kept asking questions. (I never wore earrings on assignment again.)

‘Glad You Made It’

When I came back to town as a real reporter, I screwed up my courage and reminded him of the interview. He grinned and said, “Glad you made it.” And he would call on me sometimes when a group of reporters was allowed into the Oval Office for a few questions.

All through the funeral weekend, I kept thinking about that day, and wishing I could go back to that moment, to that little tram, and I could say to him as he handed me back the fake gold coiled earring, “Mr. Kennedy, please, please, don’t go to Dallas in 1963! Don’t go to Dallas! They will kill you!”

When the rites were was over, Alan and I walked along the emptied Pennsylvania Avenue. The light was fading, it was cold and darkness would soon descend. A sailor walked by, his peacoat collar turned up against the wind and his shoulders hunched in grief.

The world had stopped for a time, but then went on; Alan and I continued with our lives. Would those lives have been different without JFK? I can’t say for sure, but certainly his call to service, his belief that government (and journalism) were forces that could change the world, became entangled in our own DNA.

Among the things Alan was proudest of is a marker that stands in Boston which bears his name. His reporting for the Boston Globe was a significant factor in the scrapping of the Inner Belt, a six-lane highway loop which would have torn through Boston’s urban neighborhoods and displaced thousands of residents.

Much of my own writing has been about people fighting for rights delayed; blacks, Vietnam vets, gays and lesbians and, of course, women. I’m proud to have been included, a few years ago, in a volume titled “Feminists Who Changed America.”

And we lived to see so much change: the civil rights laws, Title IX that gave women equal educational resources and a campaign in which a woman and an African American man could seriously contend for the presidency. Now, marriage equality seems unstoppable.

Few of these things were imaginable when JFK called us to service. And even if he didn’t have women in mind, we indeed believed he was talking to us.

Caryl Rivers is a professor of journalism at Boston University. Her novel “Camelot” has been republished as an e-book by Diversion press.

Would you like to Comment but not sure how? Visit our help page at https://womensenews.org/help-making-comments-womens-enews-stories.

Would you like to Send Along a Link of This Story? https://womensenews.org/story/our-history/131120/jfk-and-women-heres-the-uplifting-side-story