Many moons ago during the middle of the twentieth century (before the gender expansion of today), learning to look and act like a proper young lady involved being self-effacing, self-limiting and docile. In my current lectures, when I tell my story of growing up more than a half-century ago, the younger women in the audience always roll their eyes in disbelief, while their elders nod at me in agreement and understanding, remembering their own all-to-similar experiences.

One account of growing up female in the 1950s was taped in a two-minute video interview with Letty Cottin Pogrebin, whose story is very much like mine. We both learned that ladylike postures, specifically with legs crossed either at the knees or ankles, and hands in lap, were typically mandatory for a female in mid-century society. But female restrictions went deeper than just posture, as we accepted the cultural norm of displaying deference to men in words and demeanor.

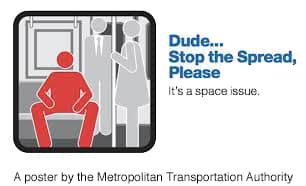

Showing this kind of deference was de rigueur for me growing up, as it was for Letty. Little girls were trained in mundane and monumental ways to take constricting, shrinking postures while boys were told to enlarge themselves and claim extra territory. This became such an unconscious reflex-action for girls wanting to fit in with their peers that the cultural pull was hard to counter.

One woman who dared to confront this norm describes how a male photographer came to her classroom of seven-year-old students to take their class picture. He adamantly insisted, despite this teacher’s protest, that each boy should sit in the chair like a “Captain,” with arms firmly set on arm rests, reaching out and forward toward the viewer, and with legs assuming the wide stance of one ankle overlapping the other knee, taking up additional horizontal space as well. The girls, on the other hand, were instructed by the photographer to sit demurely with legs crossed at the ankle, and hands folded onto their laps.

Two details from Linda Stein tapestry in her Sexism series

It was expected that this positioning, distinguishing boys from girls, would be accepted by the class without protest. But this teacher surprised the photographer by not giving ground, even to his rising anger, as we see in Daphne Harwood’s video.

It’s not unusual to see a man win an argument or get his way by raising his voice and getting angry. I saw it over and over as I grew to womanhood (even with my own father), and more recently during the Kavanaugh/Basey-Ford hearings. Emma Brockes expressed those hearings well in her recent column when she said:

“One of the discussion points to have come out of the Brett Kavanaugh hearings has been the question of anger and what women do with it – specifically, where and how they manage to stuff it down low so it doesn’t spill out and get them labelled as lunatics. Lindsey Graham can go the full Foghorn Leghorn; Kavanaugh can howl like a kid with his head stuck in railings; but to be heard, a woman must be demure and nonthreatening.”

Demure, nonthreatening –– and deferential: That’s what I learned to be as a young girl. Boys, it seemed to me, required a great deal of ego-building.

By the age of twelve, when I had my first real boyfriend, I knew how to make him feel better, stronger, smarter than me. Although a gifted athlete, I managed always to lose: I intentionally threw the bowling ball into the alley gutter and ping pong or tennis ball into the net. Losing, I learned, was the price to pay for popularity. The boy had to win. I thought that no self-respecting girl would want to be with a boy who wasn’t above her. And no boy would want a girl better than he.

And so, I was raised to take my place as a proper girl in our patriarchal society. I was contained, submissive and domesticated. I thought I would surely marry, have three children, and encourage my husband’s success. His ego, or any masculine ego, had precedence over mine. I mastered a wide-eyed look of adoration for my boyfriend as I said ‘Wow, you’re a plumber. Tell me about it. What do you do with faucets and drains?”

In my family, education wasn’t important for a girl; in fact, it could only get in the way of marriage. If I were intimidating or too smart, no boy would want me. To be desirable, I learned to balance my love for school with choosing a non-threatening (read “woman’s”) profession. I became a teacher. That was best, I was told, because it gave me “something to fall back on.” If my husband became ill or if I wanted to work after my children grew up, it was ideal. Since I loved making art, I became an art teacher.

And yet, though far from cognizance or articulation, thoughts and feelings kept cropping up: something wasn’t right. I needed answers for undefined questions. Why did I have to act differently when a boy entered the room? Why couldn’t I be proud of my education and abilities and not have to hide them? Was I signing my paintings “Linda J” (replacing “Stein” with my middle initial) in wait for my husband’s last name and his life (which would then become my life)? Why did society give boys so much more mobility, authority and respect, and why did girls accept such an unfair double standard?

When I asked a gym teacher at Music and Art High School why there was no female tennis team, he said it was because “tennis was bad for a girl’s heart.” But the absurdity of his answer didn’t register with me even though I played tennis for three hours every day after school without having a heart attack! These inconsistent sound bites went on as I grew up. At Pratt Institute graduate school, I said to an art teacher that I was going for a doctorate. He replied, ‘Why go for a doctorate? Why not just marry one?” Once again, I didn’t connect the dots. But the contradictions kept juggling in the back of my mind.

Practicing deference slowly began to grate on me. Gradually I saw that the gender rules of our society were mostly one-sided. I realized that I couldn’t fulfill my potential while putting so much effort into catering to the needs of another person.

I began to watch myself as if I were outside myself. With a male present, I saw that I spoke in a softer, cutesy voice, with less confidence. I had fewer opinions and hardly ever contradicted his manly assertions.

I sat in a constrained manner, cross-legged, poised and pretty, as if waiting to be discovered. I tended to fuse with my projection of male needs and desires. (If I thought a man were seeking a sexual liaison, I would automatically become more flirtatious and seemingly available, even if I were in a monogamous relationship and not really interested in any pursuit). I felt an invisible lid on my head, allowing me to go only so far and no further. I began to feel denied the freedom to hit the metaphorical ball as hard as I could, and, damn it, try to win!

Detail of Legs Together and Apart 925. The artist always modifies the comic’s original bubble text to address Gender Justice and Diversity

Slowly, with determination and the support of feminist writers, friends and therapy, the dots began to connect and I gradually started to change my behavior. It was difficult for me to give up the status of sex object since I didn’t know what would take its place.

But, with effort, I stopped trying so hard to please men. It helped me to ask myself if I would talk or behave the same way with a woman. My goal was to be as equally “real” in the company of either gender.

So, now, am I totally free of this Deference Syndrome? Am I as outspoken and confident with men as I am with women? Do I always try to win at ping pong?

My answer is a qualified “Yes,” though I know from reflecting on my behavior that I still have to carefully monitor my propensity to defer to men. I still struggle with my tendency to feel less important in their presence. I continue to need to remind myself to be confident and proud of my strengths and abilities.

Will relating freely and equally with men ever feel totally natural to me? These days, at least, I’m certainly hitting the ball over the net –– and winning.

Do you have a related story to tell? If so, please contact Linda Stein: Linda@lindastein.com or HAWT@haveartwilltravel.org

Linda Stein is a feminist artist, activist, educator, performer, and writer. She is the Founding President of the non-profit Have Art: Will Travel! Inc (HAWT) for Gender Justice, addressing bullying and diversity. HAWT currently oversees The Fluidity of Gender: Sculpture by Linda Stein (FoG) and Holocaust Heroes: Fierce Females – Tapestries and Sculpture by Linda Stein (H2F2), two traveling exhibitions with educational workshops. Two more exhibitions will travel soon: Displacement from Home: What to Leave, What to Take (DC4) and Sexism and Masculinities/Feminities: Exploring, Exploding, Expanding Gender Stereotypes (SMF). In 2018, Stein was honored as one of Women’s eNews’ 21 Leaders for the 21st Century. In 2017, Stein received the NYC Art Teachers Association/UFT Artist of the Year award, and in 2016, she received the Artist of the Year Award from the National Association of Women Artists.

Linda Stein is a feminist artist, activist, educator, performer, and writer. She is the Founding President of the non-profit Have Art: Will Travel! Inc (HAWT) for Gender Justice, addressing bullying and diversity. HAWT currently oversees The Fluidity of Gender: Sculpture by Linda Stein (FoG) and Holocaust Heroes: Fierce Females – Tapestries and Sculpture by Linda Stein (H2F2), two traveling exhibitions with educational workshops. Two more exhibitions will travel soon: Displacement from Home: What to Leave, What to Take (DC4) and Sexism and Masculinities/Feminities: Exploring, Exploding, Expanding Gender Stereotypes (SMF). In 2018, Stein was honored as one of Women’s eNews’ 21 Leaders for the 21st Century. In 2017, Stein received the NYC Art Teachers Association/UFT Artist of the Year award, and in 2016, she received the Artist of the Year Award from the National Association of Women Artists.

I’ve received many responses to my 6/26/18 Womens eNews article, Legs Together and Apart, and would like to continue to share some of the 2-minute video interviews that were made with these responders. Please feel free to email me, and describe your own story, so that in future articles we can make generational comparisons.