(WOMENSENEWS)–The low priority given to programming was reflected in who was assigned to the task. Although the ENIAC (the first general-purpose electronic computer) was developed by academic researchers at the University of Pennsylvania’s Moore School of Electrical Engineering, it was commissioned and funded by the Ballistics Research Laboratory of the U.S. Army.

(WOMENSENEWS)–The low priority given to programming was reflected in who was assigned to the task. Although the ENIAC (the first general-purpose electronic computer) was developed by academic researchers at the University of Pennsylvania’s Moore School of Electrical Engineering, it was commissioned and funded by the Ballistics Research Laboratory of the U.S. Army.

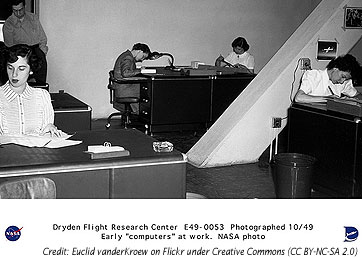

Located at the nearby Aberdeen Proving Grounds, the laboratory was responsible for the development of the complex firing tables required to accurately target long-range ballistic weaponry. Hundreds of these tables were required to account for the influence of highly variable atmospheric conditions (air density, temperature, etc.) on the trajectory of shells and bombs. Prior to the arrival of electronic computers, these tables were calculated and compiled by teams of human “computers” working eight-hour shifts, six days a week.

From 1943 onward, essentially all of these computers were women, as were their immediate supervisors. The more senior women (those with college-level mathematical training) were responsible for developing the elaborate “plans of computation” that were carried out by their fellow computers.

In June 1945, six of the best human computers at Aberdeen were hired by the leaders of the top secret “Project X ” — the U.S. Army’s code name for the ENIAC project — to set up the ENIAC machine to produce ballistics tables. Their names were Kathleen McNulty, Frances Bilas, Betty Jean Jennings, Elizabeth Snyder Holberton, Ruth Lichterman and Marlyn Wescoff. Collectively they were known as “the ENIAC girls.” Today the “ENIAC girls” are often considered the first computer programmers. In the 1940s, they were simply called coders.

<

<

The use of the word coder in this context is significant. At this point in time the concept of a program, or of a programmer, had not yet been introduced into computing. Since electronic computing was then envisioned by the ENIAC developers as “nothing more than an automated form of hand computation,” it seemed natural to assume that the primary role of the women of the ENIAC would be to develop the plans of computation that the electronic version of the human computer would follow. In other words, they would code into machine language the higher-level mathematics developed by male scientists and engineers.

Coding implied manual labor, and mechanical translation or rote transcription; coders were obviously low on the intellectual and professional status hierarchy. It was not until later that the now-commonplace title of programmer was widely adopted.

The verb “to program,” with its military connotations of “to assemble” or “to organize,” suggested a more thoughtful and system-oriented activity. Although by the mid-1950s the word programmer had become the preferred designation, for the next several decades programmers would struggle to distance themselves from the status (and gender) connotations suggested by coder.

The first clear articulation of what a programmer was and should be was provided in the late 1940s by Goldstine and von Neumann in a series of volumes titled “Planning and Coding of Problems for an Electronic Computing Instrument.” These volumes, which served as the principal (and perhaps only) textbooks available on the programming process at least until the early 1950s, outlined a clear division of labor in the programming process that seems to have been based on the practices used in programming the ENIAC.

P>  Goldstine and von Neumann spelled out a six-step programming process: (1) conceptualize the problem mathematically and physically, (2) select a numerical algorithm, (3) do a numerical analysis to determine the precision requirements and evaluate potential problems with approximation errors, (4) determine scale factors so that the mathematical expressions stay within the fixed range of the computer throughout the computation, (5) do the dynamic analysis to understand how the machine will execute jumps and substitutions during the course of a computation, and (6) do the static coding.

Goldstine and von Neumann spelled out a six-step programming process: (1) conceptualize the problem mathematically and physically, (2) select a numerical algorithm, (3) do a numerical analysis to determine the precision requirements and evaluate potential problems with approximation errors, (4) determine scale factors so that the mathematical expressions stay within the fixed range of the computer throughout the computation, (5) do the dynamic analysis to understand how the machine will execute jumps and substitutions during the course of a computation, and (6) do the static coding.

The first five of these tasks were to be done by the “planner,” who was typically the scientific user and overwhelmingly was frequently male; the sixth task was to be carried out by coders.

Coding was regarded as a “static” process by Goldstine and von Neumann — one that involved writing out the steps of a computation in a form that could be read by the machine, such as punching cards, or in the case of the ENIAC, plugging in cables and setting up switches. Thus, there was a division of labor envisioned that gave the highest-skilled work to the high-status male scientists and the lowest-skilled work to the low-status female coders.

As the ENIAC managers and coders soon realized, however, controlling the operation of an automatic computer was nothing like the process of hand computation, and the Moore School women were therefore responsible for defining the first state-of-the-art methods of programming practice.

Programming was an imperfectly understood activity in these early days, and much more of the work devolved on the coders than anticipated. To complete their coding, the coders would often have to revisit the underlying numerical analysis, and with their growing skills, some scientific users left many or all six of the programming stages to the coders. In order to debug their programs and distinguish hardware glitches from software errors, they developed an intimate knowledge of the ENIAC machinery.

“Since we knew both the application and the machine,” claimed ENIAC programmer Betty Jean Jennings, “as a result we could diagnose troubles almost down to the individual vacuum tube. Since we knew both the application and the machine, we learned to diagnose troubles as well as, if not better than, the engineers.” In a few cases, the local craft knowledge that these female programmers accumulated significantly affected the design of the ENIAC and subsequent computers.

Would you like to Comment but not sure how? Visit our help page at https://womensenews.org/help-making-comments-womens-enews-stories.

Would you like to Send Along a Link of This Story?

Nathan Ensmenger is Assistant Professor of the History and Sociology of Science at the University of Pennsylvania.

For more information:

The Computer Boys Take Over: Computers, Programmers, and the Politics of Technical Expertise (History of Computing):

http://www.powells.com/partner/34289/biblio/9780262050937?p_ti