(WOMENSENEWS)–Anasia, a 7-year-old with a light-brown complexion, slim body, bright, black marble eyes and a vibrant smile, zealously took the lead in clearing the gym of boys and men when it was our time to play.

(WOMENSENEWS)–Anasia, a 7-year-old with a light-brown complexion, slim body, bright, black marble eyes and a vibrant smile, zealously took the lead in clearing the gym of boys and men when it was our time to play.

"All right boys, pack it up," she yelled through the bullhorn one day. "It’s 4 o’clock and this is our space now. Please get dressed downstairs in the locker room."

The guys ignored her at first. Before I, as her program supervisor, could move in to help out, Mr. Al Vann, a neatly dressed, older black gentleman whom I had never met but often saw coaching local, elite players, and whose daughter was an exceptional player at Duke University, stopped his instruction and shouted, "You heard them, pack it up."

The men and boys alike did just that and followed him out of the gym as we all high-fived Anasia for clearing the gym and proceeded to set up.

Mr. Vann was an ally; he worked with our group, Girls for Gender Equity, for many years and deserved every bit of respect he was given.

Soon the mere sight of Anasia had the boys and men clearing the courts. Everything was working as planned. The Y supported our initiatives while we helped to boost their enrollment of girls under 12.

In two short months we recruited 55 girls and eight female coaches as volunteers. Everyone, including parents, responded well to all our programming and events. Having created a space where our girls were blossoming, we felt proud of the work we were doing.

Halted Sense of Progress

This feeling of progress was halted suddenly in December 2001, when an 8-year-old girl who attended school with many of our enrollees was raped on her way to school.

A man had been trailing her. She’d passed a couple of corner stores, but did not go inside. When the police later asked her why she hadn’t gone into them to seek safety, she said she didn’t want to be embarrassed and she was only a block away from school.

She pushed on and the man–smelling of alcohol and wearing red contact lenses–grabbed her and dragged her to a nearby rooftop. He brutally raped her and then fled. She managed to make it to the school before collapsing into the principal’s arms. She eventually gathered enough strength to report the rape.

As program participants met me in the gym that afternoon, they raced up to me to blurt out these awful details. I was shocked. It was so painful to hear that a child had been raped and that it had happened only 500 feet from where we lived, played and worked.

The girls and I sat around the half-court circle to share our feelings.

The girls repeated comments that they had heard from teachers, parents and peers. "She deserved it;" "She was fast;" "She shouldn’t have been alone."

I was stunned and angry, forced to confront the reality that society trains girls to internalize misogyny. Blaming the victim by identifying with the aggressor allowed the girls to distance themselves from her, thereby gaining a false sense of security.

A Lack of Compassion

The fact that the child was able to walk to school, bleeding and crying after being raped, without anyone stopping her to ask, "What’s wrong?" or "Are you okay?" told our girls that people had no compassion for abused black girls. It also communicated to our girls that if they were seen as weak or vulnerable, they were powerless against an attack.

Although the victim looked like them, went to their same school and did the same things they did daily, she must have done something wrong to bring this on herself.

In that circle, I pressed the girls to hear themselves and to see that the man’s crime was not being acknowledged.

After an hour and 15 minutes, one child said with stern conviction: "That’s why she shouldn’t be fast, wearing them clothes, act like a woman be treated like a woman."

I was caught off guard and handled the situation badly by ending the conversation with a disapproving 15-minute speech countering every one of their points. Then I sent the girls home. That night I felt defeated.

I face an extremely difficult question: Could Girls for Gender Equity really effect change?

All I could think about was how this 8-year-old baby had walked to school bleeding and disheveled without anyone asking her if she needed help. She was only visible to the man who wanted to rape her. A puppy roaming the streets would never have gone unnoticed if it were bleeding. This rape received little media coverage or community response. Many adults in the neighborhood did not know about it until I told them.

The facts of this rape, and the lack of community response, were my gut check: doing nothing was not an option.

Would you like to Comment but not sure how? Visit our help page at https://womensenews.org/help-making-comments-womens-enews-stories.

Would you like to Send Along a Link of This Story?

https://womensenews.org/story/books/110514/schoolgirls-can-find-protection-in-title-ix

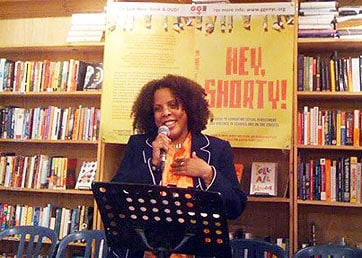

Joanne N. Smith is founder and executive director of Girls for Gender Equity, a girls’ advocacy group in Brooklyn, N.Y, and the co-author of "Hey, Shorty!: A Guide to Combating Sexual Harassment and Violence in Schools and on the Streets."

For more information:

Hey, Shorty!: A Guide to Combating Sexual Harassment and Violence in Schools and on the Streets

http://www.powells.com/partner/34289/biblio/9781558616691?p_ti

Hey, Shorty! on the Road:

http://www.heyshortyontheroad.com

Girls for Gender Equity:

http://www.ggenyc.org/