ALBUQUERQUE, N.M. (WOMENSENEWS)–Arizona may have been grabbing national attention for its anti-immigrant legislation, but in this city of at least 61,000 recent immigrants, life is also fearful for those who might be mistaken for the undocumented.

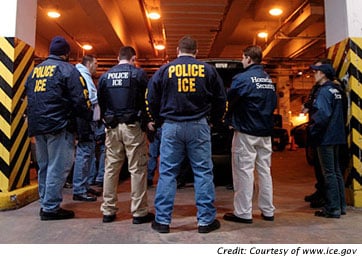

Among women suffering from domestic violence, fears have been heightened since May when the Department of Homeland Security’s Immigrations and Customs Enforcement officers began sharing workspace with local law enforcement. Now, some targets of violence worry that seeking police protection could be the first step toward deportation.

At the end of April, Immigration and Customs Enforcement–commonly called ICE–had 287 agreements with 71 law enforcement agencies in 26 states. Under these programs the federal agency delegates immigration enforcement authority to local police departments.

In May, Albuquerque Mayor Richard Berry added to that tally when he announced that ICE will work alongside Albuquerque police at the city’s new Prisoner Transport Center. Under the mayor’s new guidelines, ICE agents will screen anyone passing through the center.

For Claudia Medina, executive director of Enlace Comunitario (which in English translates roughly to “community liaison”), a nonprofit for immigrant women who are victims of domestic violence, that’s a troubling development.

“We have been getting assurances from the police chief that they won’t call ICE on them if they are just calling to report a crime,” said Medina. “But the immigrant community doesn’t know that. They just know that ICE is housed with the police and there is a strong relationship there.”

Victims Fear Police

Medina says undocumented immigrant women who are victims of crimes often don’t seek police assistance, because they fear the police are going to send them to ICE and they will be deported. Many also fear that if they report their abuser and he is undocumented, he will be deported and his income and financial support for their children will disappear, she says.

Because of victims’ fear of police contact, Medina says it’s often a neighbor, not a victim, who places the 911 call.

When police arrive, Medina says they often find a chaotic situation. “She is hysterical, crying, and he is too–you know, like screaming and yelling–and all of them are speaking Spanish. The police don’t know what’s going on, so they say, ‘That’s it, I’m taking you both.'”

Both the abuser and victim end up at the Prisoner Transport Center, where, under the new procedure, ICE will check the immigration status of both people.

In this scenario, a victim who should receive assistance, says Medina, could end up being detained and deported–in which case both parents would be separated from the children, who may be U.S. citizens.

Undocumented immigrants detained in New Mexico are sent to two different facilities along the border, and joined by those from Texas. The two facilities, one in El Paso and one in New Mexico, each have a capacity of 1,000. Since Albuquerque’s procedure is so new, no one is sure how many additional deportations may be occurring under the new police-ICE partnership.

“It’s a basic human right to be able to call for help when you are being victimized,” said Medina. If a dog is being mistreated, she says, someone can call and an officer will remove the animal from danger. “Well, we’re talking human beings here and they cannot even call for help. They cannot even get the basic right of being protected. And I think that’s not fair.”

Shelters Not an Option

As in many cities, housing programs in Albuquerque for victims of domestic violence cannot help women without immigration papers; even homeless shelters will not accept undocumented immigrants.

Jessica Aranda, an Albuquerque native and activist for the rights of women and immigrants, echoes Medina’s concerns about the new local ICE program’s effect on immigrant women, an already vulnerable population.

“That’s going to be a huge issue for immigrant women or women who have immigrants in their family, to feel like police are a resource when there is violence happening in their families,” said Aranda. “That will definitely play into the whole dynamic of further disenfranchisement for women of color.”

Albuquerque City Councilman Ken Sanchez was one of the city council members who tried to block police involvement with ICE. Their resolution failed and council members who backed it said they received hate e-mail.

Sanchez agrees with Aranda that someone who is already uncomfortable with the police might feel further threatened by the new procedure.

“That was a very big concern of mine when the mayor passed this legislation,” said Sanchez. “He wants to make sure that we are keeping our community safe and keeping criminals off the street . . . Well, especially in a domestic-violence case, these women may be afraid to call 911, if they themselves or their children are being abused by a spouse.”

He adds that if women fear deportation, they may not call for help. “That is one of the real concerns that I have with this legislation,” he said. “The mayor has assured that that would not be the case.”

‘Nothing Will Change’

At a recent city council meeting, Sanchez invited Albuquerque Police Department Chief Ray Schultz to the podium, asking him what will change with the new procedure. “He said, ‘Nothing will change at all with APD,'” said Sanchez.

As a result of an earlier court challenge, beginning in 2007, the Albuquerque Police Department could not question someone’s immigration status unless it was relevant to a criminal investigation or a person had already been arrested. “And the chief reaffirmed that to be the case,” said Sanchez.

Schultz has repeatedly said that officers themselves would not be checking the immigration status of individuals and the mayor has claimed racial profiling will not occur–that everyone, regardless of nationality, race or language, will be screened.

The procedure isn’t entirely new, says Jennifer Landau, an attorney with Diocesan Migrant and Refugee Services. She points out that for a few years ICE officials have had a presence at the Metropolitan Detention Center.

“But they’re casting a wider net now, because everyone that is arrested in Albuquerque is going to be screened and interviewed by ICE–before it was just at the local jail,” she said.

Landau adds that Albuquerque isn’t unique: “This isn’t totally new, but it is a part of a national trend.”

In April, Arizona Gov. Janet Brewer signed into law a state Senate bill requiring police officers to check the immigration status of anyone they suspect is an undocumented immigrant. It also makes it a state crime to be in the United States illegally.

Despite the federal government’s opposition to the law–the Obama administration has sued, claiming the law is inconsistent with federal policy–more states are considering laws similar to that of Arizona.

Legislatures in five states have already introduced bills. In another 15, they’re under discussion. And on a local level many police departments, like the one here, are cooperating with the Department of Homeland Security’s ICE.

Would you like to Comment but not sure how? Visit our help page at https://womensenews.org/help-making-comments-womens-enews-stories.

Laura Paskus is an independent journalist working on a series of stories about vulnerable and exploited women in Albuquerque; that work that has been funded in part by an investigative research grant from the nonprofit Center for Civic Policy.

For more information:

Albuquerque-based Enlace Comunitario:

http://www.enlacenm.org/

“Mapping the Spread of SB 1070”:

http://colorlines.com/archives/2010/06/mapping_the_nationwide_spread_of_arizonas_sb_1070.html

Teach-In Toolkit from the National Immigration Law Center:

http://www.nilc.org/immlawpolicy/LocalLaw/uncover-truth-toolkit-2010-05.pdf